From Headlines to Algorithms: How News Is Being Filtered Before You See It

The way people consume news has changed dramatically over the past decade. While headlines once arrived through newspapers, television broadcasts, or bookmarked websites, today most news is delivered through algorithms. Social platforms, search engines, and news apps now decide what stories appear, when they appear, and how prominently they are displayed. This shift has quietly transformed not only how news is distributed, but how it is filtered before audiences ever see it.

At the core of this transformation are algorithmic recommendation systems. These systems analyze user behavior—what is clicked, shared, watched, or ignored—and use that data to predict what content will keep users engaged. News stories are no longer prioritized solely by editorial judgment or public importance, but by relevance signals generated through user interaction. As a result, two people following the same news platform may see entirely different versions of the day’s events.

This personalization has clear advantages. Algorithms can surface stories aligned with individual interests, reduce information overload, and make news consumption more efficient. For busy readers, curated feeds can feel helpful, offering quick access to topics they care about most. In theory, this creates a more engaging and accessible news experience.

However, algorithmic filtering also raises concerns about fragmentation. When users are consistently shown content that aligns with past behavior, exposure to diverse perspectives can narrow. This phenomenon, often described as “filter bubbles,” limits the range of viewpoints people encounter. Over time, this can reinforce existing beliefs and reduce opportunities for shared understanding across audiences.

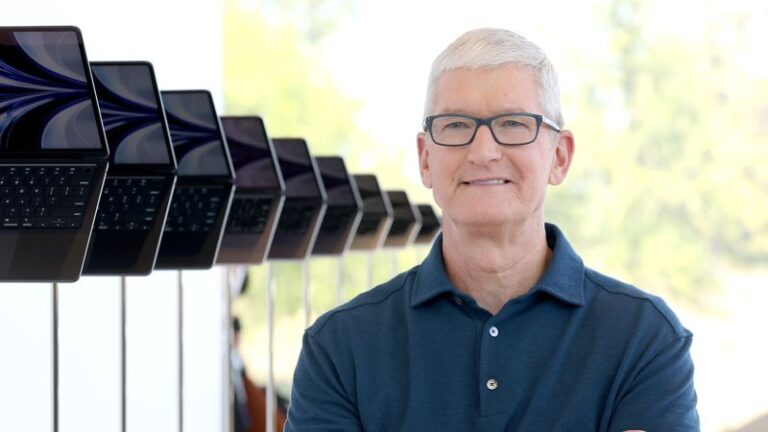

Editorial priorities are also affected by algorithmic distribution. News organizations must consider how their content performs within platform systems. Headlines, formats, and story placement are often optimized to satisfy algorithmic preferences, such as engagement metrics or watch time. This can blur the line between editorial judgment and platform-driven incentives, subtly influencing what stories are told and how they are framed.

The rise of automated filtering has implications for breaking news as well. Algorithms favor content that gains traction quickly, which can amplify unverified or sensational stories before facts are fully established. While platforms have implemented moderation tools and ranking adjustments, speed often competes with accuracy. In this environment, misinformation can spread faster than corrections.

Transparency remains a key challenge. Most platforms provide limited insight into how their algorithms rank and prioritize news. Users rarely know why certain stories appear in their feeds while others do not. This opacity makes it difficult to assess bias, accountability, or editorial responsibility. As algorithms increasingly shape public discourse, calls for transparency and oversight continue to grow.

Journalistic institutions are responding in different ways. Some outlets invest in direct distribution channels such as newsletters and apps to regain control over audience relationships. Others experiment with hybrid models that blend algorithmic reach with human curation. These efforts reflect a broader attempt to balance reach with editorial independence.

From a societal perspective, algorithmic news filtering shifts power away from traditional gatekeepers and toward technology platforms. Decisions once made by editors are now influenced by code, data, and user behavior at scale. While this democratizes distribution in some ways, it also concentrates influence within a small number of platforms that shape information flows globally.

Looking ahead, the future of news will likely involve ongoing negotiation between algorithms and human judgment. Technology will continue to play a central role in distribution, but trust will depend on how responsibly that technology is used. Audiences increasingly value credibility, transparency, and context—qualities that algorithms alone cannot provide.

As headlines give way to feeds, understanding how news is filtered becomes essential. The question is no longer just what is happening in the world, but how—and why—we are seeing certain stories at all. In an algorithm-driven media landscape, media literacy is no longer optional. It is a necessary skill for navigating modern news.